Today, at the height of my retirement and in as respectable an appearance as that to which I am now capable to attach, I presented myself to a country lawyer in our small town to sign an affidavit regarding a will I had drawn over a decade ago. It is a longstanding distinction to be a country lawyer – a distinction which, sometimes jokingly, others times mockingly, brooks either complimentary status or pejorative contempt. Predominantly however it may be displaced as a term of endearment. For my part it is an epithet to which I bond with considerable zeal and pride and no false modesty. I have heard it said of one country lawyer no longer whinnying among us that, “He practiced law with the contempt it deserves!” This from a former Justice of the provincial court in our county seat. The labelling competition is normally among the lawyers themselves.

Historically, such an attorney (a country lawyer) may have been more likely to have joined the bar by reading law rather than attending school, and in modern times may have (or may be assumed to have) graduated from a lower tier legal program. The professions of law and medicine had this in common in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as country doctors of that day sometimes trained by “reading medicine” with established doctors, effectively in an apprenticeship, with minimal or no medical school training and hospital residency.

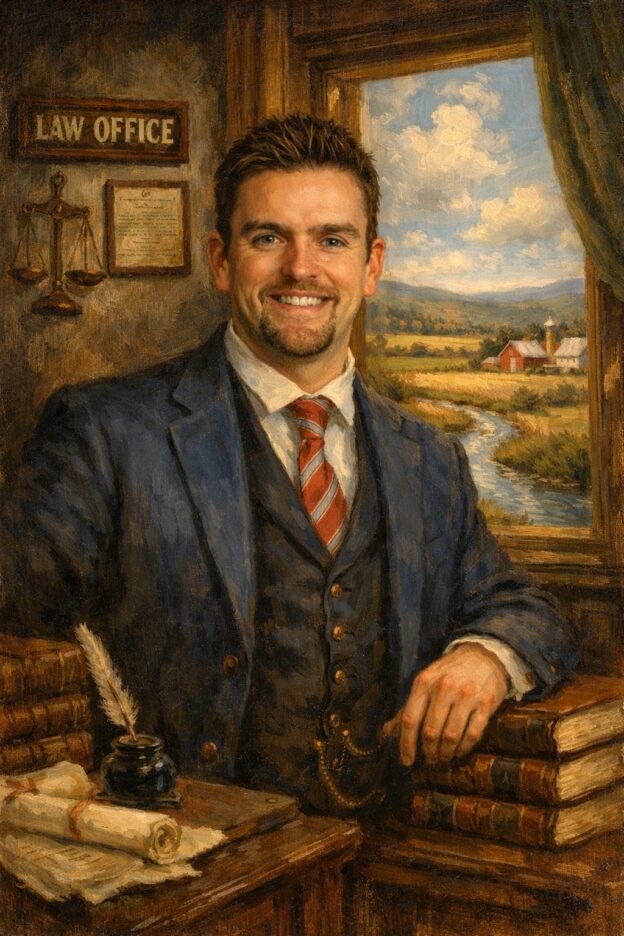

The refinement of the colloquial was borne out today by the fact that the country lawyer with whom I met was also a city lawyer in a law firm of other lawyers. The term, big city lawyer, may carry slighting connotations. Nonetheless my encounter today with the country lawyer was, as I discovered, both enlivened and enhanced by his rural family and upbringing on a 400-acre farm not far from the adjoining county town where he and his immediate family reside.

Monopolizing upon my entitlement as an historic rural practitioner, I used the occasion of our meeting today to project my casual thoughts. Remarkably I called upon my sense of hearing – one which I gleefully pronounced related to the ability to play the piano by ear – to compliment the country lawyer. As I told him, from the moment I first heard his voice I recognized what I decipher as the characteristic traits of a country lawyer, among them a softness of address combined with a buoyancy of theme and – if I may be forgiven to lapse into Emily Post’s Book of Etiquette – a calculable discretionary overtone commonly called respect for old age. Unsurprisingly the country lawyer maintained this obvious restraint when addressing a number of other matters, a focus which I found both chivalrous and invigorating.

The attraction to country lawyers is not limited to literary, audible or theatrical motives. I have often recalled the assurance of a former client who was part of a celebrated entrepreneurial family in the Village of Dunrobin, Ontario. She unhesitatingly avoided big city lawyers in preference for country lawyers. Granted she had grown up in a rural environment and then lived in an estate along the Ottawa River as did her immediate family and in-laws. But rural residency is not the sole force behind the country lawyer. I quickly learned in my practice that many people had turned their heads to the farming scene in preference for the urban vernacular. Though I am quick to recall as well that when, as happened on more than one occasion, I was consulted about a matter clearly beyond my intelligence and capacity, my client and I together attended upon a big city lawyer for enlightenment. The big city lawyer – to his credit – knew enough to complete the retainer without encouraging any shift of allegiance, a candid division of power which effectually maintained the community in the future.

Call it what you will, it may amount to no more than a distinction without a difference. Remember the sobering adage, “The only thing worse than a lawyer at a party is two of them!”

Accordingly I bow.

The Country Lawyer

Today, at the height of my retirement and in as respectable a state as I can now manage, I presented myself to a country lawyer in our small town to swear an affidavit concerning a will I drafted more than a decade ago. It remains a small but enduring distinction to be a country lawyer—a title that, depending on who utters it and with what inflection, can serve equally as compliment, mockery, or affectionate tease. For my part, I embrace it without apology or false modesty.

I once heard a former Justice of our provincial court remark of a now-departed country lawyer, “He practised law with the contempt it deserves.” The line has circulated ever since, traded almost lovingly among lawyers themselves.

Historically, the country lawyer was more likely to have entered the profession by reading law than by attending a formal school, just as country doctors once learned their craft by apprenticing themselves to established physicians. Both callings, in their rural forms, grew up close to life as it was actually lived—illness, death, property, family, and dispute arriving not in abstractions but in flesh and acreage.

What refined the irony today was that the country lawyer I met is also, quite plainly, a city lawyer: a partner in a firm of many lawyers. Yet he was raised on a four-hundred-acre farm not far from the county town where he now lives, and that upbringing remains audible in him. There is, unmistakably, a country cadence—a softness of address, a buoyancy of tone, a respectful restraint that Emily Post herself might have recognized.

I told him as much, invoking my own musical vanity by explaining that I hear these things the way a pianist hears pitch. From the moment he spoke, I knew what he was. Not merely competent, but attentive. Not merely professional, but chivalrous in that quiet, rural way that never advertises itself.

My fondness for country lawyers is not merely sentimental. Years ago a client of mine from a celebrated entrepreneurial family in Dunrobin, Ontario, insisted on them almost to the point of doctrine. She and her kin lived along the Ottawa River on old estates, yet she had little patience for big-city counsel. Over time, I found she was not alone. Many clients, even those who had migrated to urban life, preferred the rural lawyer’s manner: steadier, less theatrical, less enamoured of his own cleverness.

That is not to say there is no place for the big-city lawyer. When a matter exceeded my own intelligence or experience—as it sometimes did—I would take the client myself to one. The best of them knew to take the retainer without poaching the relationship. That quiet division of labour preserved both dignity and community.

Call it what you like. Perhaps it is a distinction without a difference. Still, one should never forget the old truth: the only thing worse than a lawyer at a party is two of them.

Accordingly, I bow.