An article by Louisa Clarence-Smith (US business editor at The Times) has been forwarded to me by my erstwhile physician. The article is about the well known southern business called Cracker Barrel.

When my erstwhile physician travels to his properties in Florida, he flies. When we visit Florida on vacation, we drive. And when we do – as we have done for the past decade – we regularly stop at Cracker Barrel along the way. Cracker Barrel – not unlike many corporations – punctuates its restaurant endeavours by maintaining an underlying theme of prime real estate. Its convenient locations along i95 are only part of their success; the biscuits are nonpareil, the lemonade delicious, the main courses are reliably prepared and served.

A southern comfort food chain is attracting little sympathy after falling foul of America’s most influential corporate activist of the summer: President Trump.

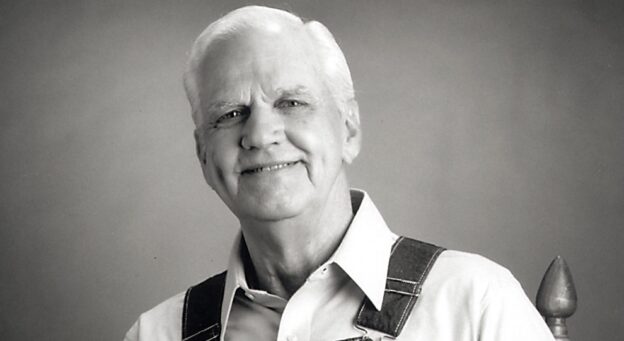

Cracker Barrel, which serves chicken ’n’ dumplins, meatloaf and country fried steak with biscuits and cornbread, finally reversed a planned rebrand on Tuesday night after a backlash over its decision to change its old logo, removing the image of an older man, “Uncle Herschel”, in overalls sitting next to a barrel and the words “Old Country Store”.

Here is the skinny on Uncle Herschel:

Uncle Herschel was Cracker Barrel Old Country Store’s founder Dan Evins’ real uncle, the younger brother of Evins’ mother. He helped shape not only Cracker Barrel’s image but also its values. He was our own “goodwill ambassador” to the public. Uncle Herschel was a wealth of knowledge about what rural America’s old country stores were really like. He was a salesman for Martha White Flour Company for 32 years, traveling the rural South calling on many towns’ general stores. Like many Cracker Barrels today, the community general stores were more than just a place to purchase goods. They were a gathering place for folks to take a timeout from the chore-filled day to visit with a neighbor or two, exchange pleasantries or just talk about the weather.

Its “country store” model – which, by the way, is so repetitive you cannot judge one outlet from another – is a model which I find to be wearying: the collection at the front of the restaurant of wooden rocking chairs (all secured by coils), the oppressive masses of glitter and pure sugar confectionary within the entrance, the racks of cheap clothing, the customarily useless fireplace, the wall hangings of garage sale relics. In short, I consider it a small compliment to preserve the identity.

My conclusion is the same as that of the author:

Instead of focusing on winning over a new, younger audience, Cracker Barrel is now scrambling to win back its Maga base.

The decision of Cracker Barrel to abandon change is, in my opinion, reflective of the American psyche generally. And, no, I don’t mean that in a nice way. What disturbs me in particular is the attempt to revitalize what is historically an infected resource. Let me put it this way: reliving the plantation days is not exactly the most healthful way of advancing society; and, whether the Americans like it or not, youth have evolving motivations and manners of expression which are no longer chained to the past.