For most of us change is moderately disturbing. We often like things the way they are. But when we feel differently about the way things are, change is not unwelcome. Yesterday – while reading an article sent to me by Prof. Daniel A. Laprès from Paris, France – I noted in particular the following blunt observation:

For the many Global South governments that are skeptical of the Western development model, China’s resilience in the face of US pressure lends credence to President Xi Jinping’s claim that the world is undergoing “great changes not seen in a century.”

Professor Daniel Arthur Laprès

Without fully appreciating the import of the many critical elements of that statement (Global South, Western development model, China’s resilience, US pressure) it is inescapable that China has become a worldwide influence possibly destined to overtake the crown of America.

Xi Jinping (born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and thus the paramount leader of China, since 2012. Since 2013, Xi has also served as the seventh president of China. As a member of the fifth generation of Chinese leadership, Xi is the first CCP general secretary born after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The son of Chinese communist veteran Xi Zhongxun, Xi was exiled to rural Yanchuan County, Shaanxi Province, as a teenager following his father’s purge during the Cultural Revolution. He lived in a yaodong in the village of Liangjiahe, where he joined the CCP after several failed attempts and worked as the local party secretary. After studying chemical engineering at Tsinghua University as a worker-peasant-soldier student, Xi rose through the ranks politically in China’s coastal provinces. Xi was governor of Fujian from 1999 to 2002, before becoming governor and party secretary of neighboring Zhejiang from 2002 to 2007. Following the dismissal of the party secretary of Shanghai, Chen Liangyu, Xi was transferred to replace him for a brief period in 2007. He subsequently joined the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) of the CCP the same year and was the first-ranking secretary of the Central Secretariat in October 2007. In 2008, he was designated as Hu Jintao’s presumed successor as paramount leader. Towards this end, Xi was appointed the eighth vice president and vice chairman of the CMC. He officially received the title of leadership core from the CCP in 2016.

The little I know about China is that collectively the people there have accomplished sometimes staggeringly efficient successes (infrastructure, technology, automation and manufacturing). Commensurately as the “great changes not seen in a century” have transpired, it has become commonplace to acknowledge the ingenuity of China. I readily confess this “development model” and “resilience” based upon no more or less than my direct personal experiences over the past 76 years. As the spectrum of world communication ever increases, I am time and again impressed by what I see coming out of China.

No longer is the label “Made in China” used mockingly. Nor – I am quick to add – is “Made in USA” any less persuasive as a result. But it cannot be denied that the rhetoric coming out of China is far more stimulating than the trap currently predominating American newspapers. There is regrettably the appearance of shameful narrowness and unwitting self-infliction of harm issuing from American alarms.

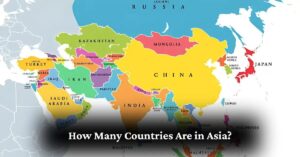

Historians will no doubt entertain themselves endlessly with the cause and effect of the modern day “fall of the Roman empire”. Already the predictions border on axiomatic – as though it were only a matter of time before power shifts from one pillar to another. While the English language may currently command the world, it is foreseeable that Mandarin (the standard literary and official form of Chinese based on the Beijing dialect) will change that particular vogue.

The English-speaking world comprises the 88 countries and territories in which English is an official, administrative, or cultural language. In the early 2000s, between one and two billion people spoke English, making it the largest language by number of speakers, the third largest language by number of native speakers and the most widespread language geographically. The countries in which English is the native language of most people are sometimes termed the Anglosphere. Speakers of English are called Anglophones.

Early Medieval England was the birthplace of the English language; the modern form of the language has been spread around the world since the 17th century, first by the worldwide influence of England and later the United Kingdom, and then by that of the United States. Through all types of printed and electronic media of these countries, English has become the leading language of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and professional fields, such as science, navigation and law.

The United States and India have the most total English speakers, with 306 million and 129 million, respectively. These are followed by the United Kingdom (68 million), and Nigeria (60 million).

Here’s a more detailed breakdown:

English: Approximately 1.53 billion people speak English, with around 360 million native speakers and over a billion as a second language.

Chinese (Mandarin): Around 1.18 billion people speak Mandarin, primarily as their native language. While Mandarin is the most spoken language by native speakers, it has significantly fewer second-language speakers compared to English.

In essence, while Mandarin is the most spoken language by native speakers, English has a broader global reach due to its widespread use as a second language.

In the interest of efficiency it would not surprise me to learn that English as a common global vernacular is both encouraged and adopted. There is no need for unnecessary obstruction to communication. Meanwhile the “great changes not seen in a century” continue to unfold. Perhaps those amused by political models – capitalism vs communism for example – will delight in the metamorphosis of global affairs. As for contradictory allegations of constitutional infringement, violation of personal freedoms and choice and other such esoteric legalities, I believe no nation is now considered to have entitlement to those proclamations.

Once again I am reminded of the diverse image of inhabitants in the cantina scene of a Star Wars movie. How far removed from our moorings must we be before acknowledging our collective ambition?

Selon Hal:

For most of us, change is moderately disturbing. We often prefer things as they are. But when dissatisfaction creeps in—when we no longer like the way things are—change loses its menace and can even become welcome.

Yesterday, while reading an article forwarded to me by Professor Daniel A. Laprès from Paris, I came across this blunt observation:

“For the many Global South governments that are skeptical of the Western development model, China’s resilience in the face of U.S. pressure lends credence to President Xi Jinping’s claim that the world is undergoing ‘great changes not seen in a century.’”

Without needing to unpack every critical element of that sentence—Global South, Western development model, China’s resilience, U.S. pressure—one cannot help but concede that China has emerged as a global force, possibly poised to inherit the crown of American primacy.

Xi Jinping (b. 1953), now the paramount leader of China, has held the titles of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Military Commission since 2012, and President of China since 2013. He is the first CCP general secretary born after the 1949 founding of the People’s Republic. The son of communist veteran Xi Zhongxun, Xi’s early life was shaped by political exile and hard labor during the Cultural Revolution. He later rose steadily through provincial and national ranks—Fujian, Zhejiang, Shanghai—before consolidating his position at the center of power.

What little I know of China comes less from scholarship than from experience—seventy-six years of reading, watching, and listening. And what I’ve observed is this: the country is staggeringly efficient in many respects—technology, infrastructure, manufacturing. The phrase “great changes not seen in a century” doesn’t strike me as hyperbole.

No longer is the label “Made in China” a punchline. Nor, I should add, has “Made in USA” lost its allure. But what cannot be ignored is that the rhetoric emerging from China is more vivid, more aspirational, more coherent, than what now dominates American discourse. By contrast, American media—particularly its newspapers—often feel narrow, disjointed, and self-sabotaging.

Historians will no doubt busy themselves with drawing parallels between this moment and the long decline of the Roman Empire. The predictions already seem to border on orthodoxy, as though it were only a matter of time before global power shifts again. While English may still command the world’s attention, it is not inconceivable that Mandarin will come to rival it, if not replace it, as the dominant language of the future.

English is currently the most widely spoken language in the world: roughly 1.53 billion people speak it, including about 360 million native speakers. Mandarin, by contrast, has about 1.18 billion speakers, primarily as a first language. The distinction matters. English spreads by function; Mandarin by birth. And in a world preoccupied with efficiency, there is reason to believe English will remain a preferred global vernacular, if only for convenience.

But language is only one arena in which change is underway. Political models—capitalism, communism, or whatever their evolving offspring may be—are less fixed than we pretend. And the once-authoritative proclamations of constitutional fidelity, personal liberty, or democratic entitlement are now as likely to draw skepticism as respect. No nation, it seems, has an unchallenged claim to moral superiority.

More and more, I find myself thinking of that famous cantina scene in Star Wars—a roomful of odd, diverse creatures trying, in their own way, to coexist. It’s chaotic, yes—but also oddly cooperative. How far must we drift from our historical moorings before we admit what binds us: a common ambition to endure, to adapt, and perhaps even to thrive together?